It seems odd in hindsight, but far from the oddest thing that happened in 2020: just over one year ago I was assembling my bike in the common room of a cheap guesthouse in Luxor.

After a summer of bikepacking adventures closer to home, it felt freshly exciting and also oddly familiar to be packing panniers and mangling a foreign language once again. International bike touring is the riding style that first ignited my obsession with bikes, and the one I keep coming back to in my bolder dreams.

It would be my third visit to the continent of Africa, though my first on a bike. A full Cairo to Cape Town ride wasn’t in the cards, but I was excited to sample a small section, see the famous archaeological sites of ancient Nubia, and experience the Islamic culture of northern Africa for the first time. I would start in Luxor and ride through the deserts of southern Egypt and northern Sudan, and maybe on to Ethiopia, before returning home to my patient husband in April.

Was it crazy to start such a trip in February of 2020, as the pandemic was already spreading in China? Viewed through the ever-shifting vortex of the past year, I’m a little surprised that I went ahead with it.

But back then, remember, we were all in denial. The first official cases had yet to be recorded anywhere on the African continent, and no one in the US was changing their behavior or their plans. My decision to go felt ordinary, in line with my usual semi-cautious approach to adventure. Surely it would all be fine.

Egypt

So, in February I found myself on a flight to Egypt with my trusty Long Haul Trucker in a cardboard box. Connecting through bustling Istanbul, a major transport hub on the massive Eurasian landmass, I savored the perspective that “over there” for me is actually “here” for a large portion of the world. It felt like I had arrived somewhere important.

Two more short flights and I was in Luxor, one of the world’s premier tourist destinations and essentially a city-sized ancient Egyptian museum.

Egypt takes some getting used to, especially on a bicycle. Few places can match its contrast between mass tourism attractions and rarely visited villages. One enterprising boy captured it perfectly as he followed me along the Nile corniche. “You want boat ride?” he pitched, followed by “Give me money,” and then “You are sexy.” When I scolded him for that last one, he smiled and said “Welcome to Luxor, have a nice day!” and sped off to find a new target. His execution needed a little refinement, but his hustle was impressive! Fortunately a bicycle makes it easy to savor the in-between places where few travelers bother to stop, which is where my experience of Egypt was most memorable.

I slipped out of Luxor in the quiet of early morning after two days exploring the incredible temples and shaking off the touts. Early in solo bike trips I often hesitate to stop; I guess I feel less vulnerable when moving. When hunger finally got the better of me and I slowed beside a falafel stand, an old man shook my hand, said “Welcome” (the only English word many Egyptians seem to know), and helped lift my bike over the curb. The delicious falafel, sludgy black coffee, and friendly words from the men seated nearby were fuel enough for the afternoon.

Police escorts are a defining feature of any bicycle tour in Egypt, and it wasn’t long before I encountered my first. Many cyclists go to great lengths to shake them off, but I had mixed feelings. True, their presence made it harder to take breaks and interact with locals. But the policemen were locals themselves, spoke more English than average, and were usually happy to interact. In a country notorious for sexual harassment, they were professional and I admit I found their presence reassuring.

I figured they’d rather follow a happy cyclist than a grumpy one, and I’d be happier if they were happy, so I offered a bag of dried dates to each new crew and tried to play the part. Some cars would leapfrog with me, cheering and pumping their fists with each pass. Others trailed directly behind at 10mph, a car full of four armed officers as my personal escort, as comical as it was annoying. On an empty stretch of highway one car pulled alongside me and we pretended to race, the driver feigning effort as we both accelerated and laughed.

From Luxor to Aswan the road followed the Nile Valley through towns and countryside. Sometimes the towns were gritty and the shouts sounded aggressive. Other times the villages were peaceful and the greetings gentle.

Being visible all day long in a country of men, always only men, was draining. For every woman out in public there were twenty men, all staring at me. I drank up the rare exchange of a smile or eye contact with women whenever I could.

The city of Aswan, sometimes known as the Gateway to Africa, had a definite melting-pot vibe. A few blocks in from the touristy Nile corniche it was all narrow alleys and chaotic streets, motley collections of vehicles vying for space, small shops on every corner selling snacks and produce. For the first time in Egypt I heard music playing in the streets that wasn’t coming from a mosque.

After two days of wandering Aswan’s bustling streets I pedaled out in the quiet of Friday, the Muslim holy day, toward Abu Simbel.

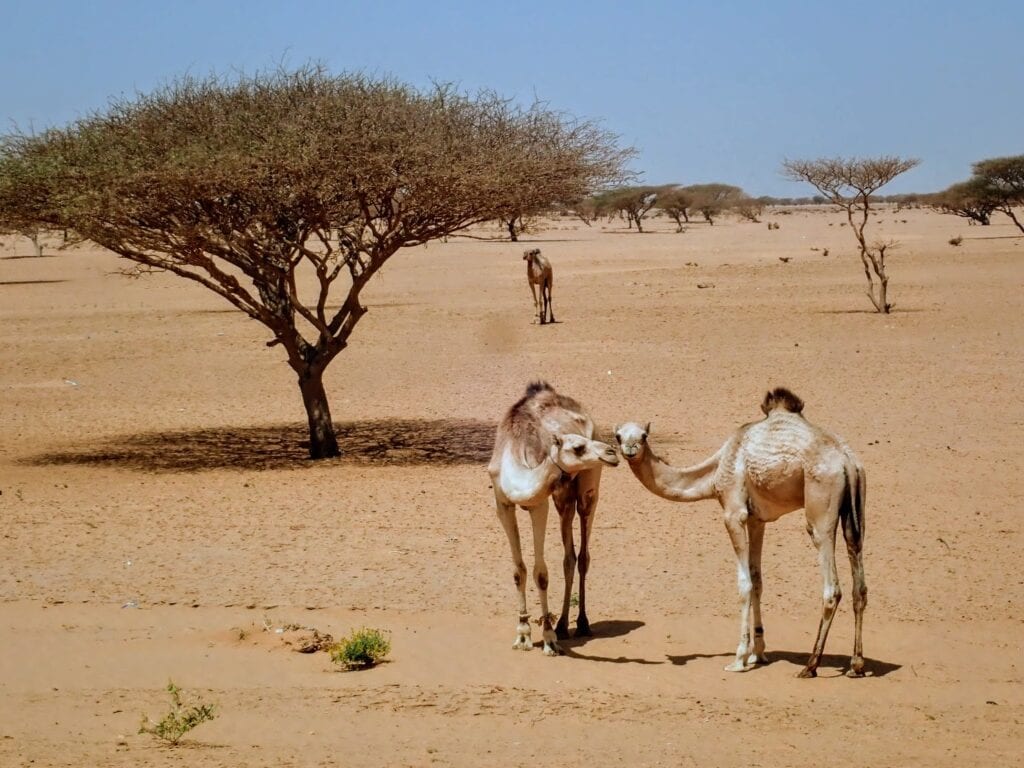

The road to Abu Simbel was straight, flat, smooth desert highway with light traffic, a hard shoulder, and a slight tailwind. It sliced through barren desert, endless sand and rocks, with no notable towns for a couple hundred kilometers. The roadside was littered with old decaying truck tires, nothing left except tangles of wires sprouting from the sand like odd desert plant life.

No pedestrians, no tuktuks, no shouts to decipher, no eyes on me constantly. In other words, bliss after the Nile Valley! I put on some music and finally found a rhythm.

With no towns along the road to Abu Simbel, my nights were spent camping at police checkpoints. Though a bit rough around the edges, they were enthusiastic hosts. Imposing during the day with their grey camo uniforms and AK-47s, in the evenings they relaxed and transformed. They often shared their evening meal, all of us crouching or standing around a communal pot and dipping bread into sauce with our right hands in polite Muslim fashion. They gave me snacks, boxes of “feta vegetable fat” spread and extra bread. I finished that stretch of highway with more food than I started with.

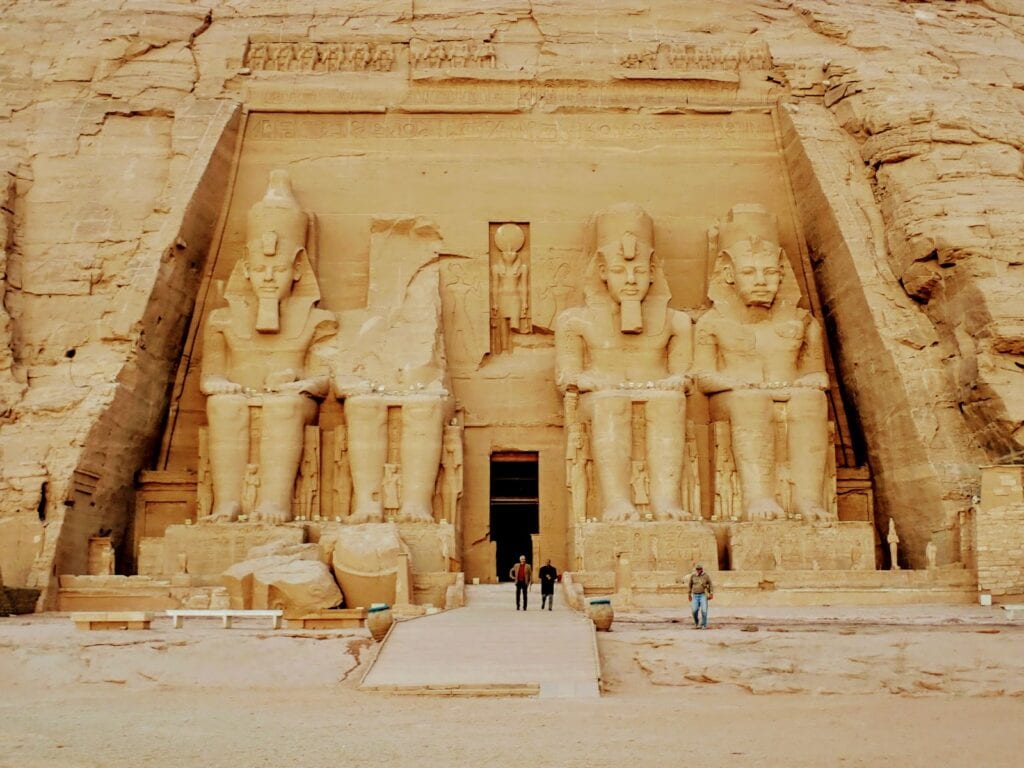

Abu Simbel is as far south as most visitors go in Egypt, and most are there to see the incredible temple on the shore of Lake Nasser. It was built (over 3000 years ago!) so that sunlight fills the inner chamber only twice each year, and when the Aswan High Dam was built the whole thing was painstakingly moved while preserving this alignment. It’s a marvel of both ancient and modern engineering.

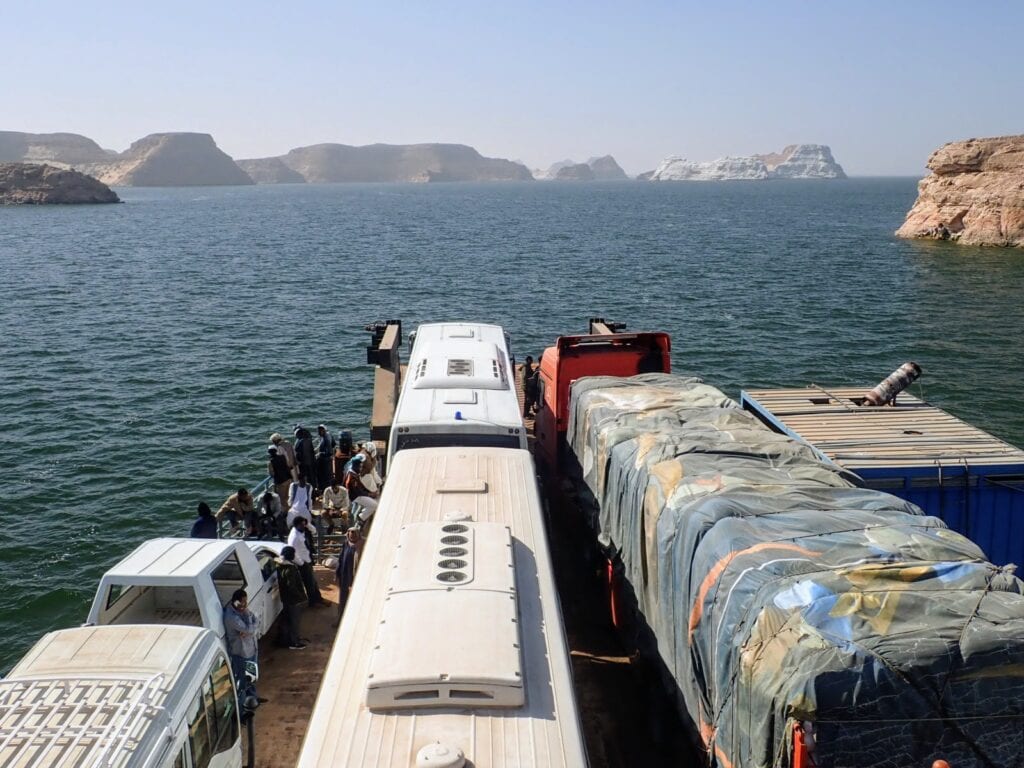

I spent a couple days in town resting up, visiting the temple, and confirming my visa arrangements for Sudan. The next morning I headed to the ferry dock for the crossing of Lake Nasser and the final 20 km to the border with Sudan.

Sudan

Sudan is notorious for its bureaucratic red tape, and the border crossing was a perfect introduction. Fortunately I had arranged for a “fixer” in advance as part of getting my visa at the land border. He handed me form after form and disappeared with my passport. After a couple hours the process still wasn’t finished and he suggested I should leave my passport with him at the border, bike to his house in Wadi Halfa, and meet him there that evening. What could possibly go wrong with that plan? But, he was adamant.

I followed him as we shoved our way toward the customs building, feeling a new kind of energy at this gateway to sub-Saharan Africa. People hefted sacks of grain out of my way and encouraged “Go! Go!” as I pushed my bike through the dense crowd. An elegant woman in a lovely purple headscarf blew me a kiss. My panniers were shuffled through a creaking x-ray machine and the crowd flowed out the doors into the desert sun. And then, I pedaled into Sudan.

Sudan had always been the focus of my trip. I’m drawn to places others avoid, especially when the only reason seems to be misinformed fear. The same curiosity that once drew me to West Africa as a backpacker now drew me to Sudan as a cyclist.

Most Cairo to Cape Town riders describe Sudan as a favorite for its easy-going friendliness, and I was certainly looking forward to that. I also wanted to learn about a misunderstood country in the midst of a political and cultural revolution, fighting its way through an economic crisis at the same time it attempts to shed decades of oppressive rule, all largely ignored by American media.

The empty desert roads of northern Sudan were a joy to ride. The wind was not to be argued with, but most often it traveled toward the south and so did I. The rare car or truck passed with a friendly honk as the men sitting on top, scarves wrapped around their faces against the desert air, raised their arms in greeting.

The visa and passport pickup worked out, of course. But first I got lost in Wadi Halfa, was mistakenly taken in at the wrong house (such is the unquestioning hospitality of the Sudanese!), redirected by a helpful neighbor (“Oh, this is Nazar’s house, he is Mazar’s cousin. I will bring you to Mazar’s house.”), and hosted for a night at Mazar’s family home.

Inspiring Encounters

Further south the highway drew closer to the Nile and the thin green ribbon of irrigated land that sustains life. A boy parked his donkey cart, crossed the road to silently shake my hand, then returned to his donkey and continued.

Soon after, a man on a motorbike sped by yelling “Yoooouuuu are welcommmme!”

And then, a car stopped and an entire family piled out, took selfies, and peppered me with questions while passing drivers maneuvered around their car in the middle of the highway. So this was the Sudan I’d heard about! I know it’s the great hypocrisy of the “off-the-beaten-track” traveler, but what a joy to visit places that haven’t been jaded by mass tourism.

My memories from Sudan are full of kindness and spontaneous connection. In Dongola a young boy latched onto me and I wondered what the catch was – did he want to sell me something? No, he aspires to be a doctor and just wanted to practice English, and see if I needed anything.

In the middle of a national bread shortage, men waiting in long lines at bakeries ushered me to the front and helped me place my order.

An old man kissed the back of my hand and said “America beautiful.” If he knew about the history of strained relations between our countries he certainly didn’t hold it against me, and he smiled widely when I answered “Sudan beautiful.”

Over and over, Sudan exemplified one of my favorite things about traveling by bike: connecting with fellow humans across lines of nationality, politics, language, and economics. Though we could rarely trade more than a few words with our combined English and Arabic, the Sudanese helped me remember the importance of hospitality, generosity, curiosity, and trust. From the receiving side the value of all this is blindingly obvious, but it’s hard to bring back home into everyday American life. Still, it helps to know there are places in the world where this is a normal way to be.

Desert Heat and Hospitality

From pleasant Dongola with its refreshing Nile breeze, the crux began: five days of desert riding across the sparsely populated Sahara, punctuated only by the town of Karima and a few isolated rest stops. As I made the left turn onto the empty highway, the police at the checkpoint warned that it was a very long way but cheerfully waved me on.

The next few days were dominated by sun, heat, and wind. The air felt like a hairdryer pointed directly at my mouth, so I wrapped my headscarf over my face to capture moisture from my breath. There was zero shade, so every few hours I sat down beside the road to choke down dry bread and Laughing Cow cheese wedges. Occasionally a minibus sped by, eager to be done with the nothingness. Audiobooks kept me going. I camped alone in the desert looking off into the endless expanse of sand and rock, an experience I’ll always treasure.

The next morning three boys came sprinting across the sand as I tried to make the most of the cooler morning hours. Completely out of breath, they met me at the road with a jumble of excited Arabic and the universal gesture, a hand held to the mouth: would I like to drink tea? They signaled that I should follow them to a small building in the distance.

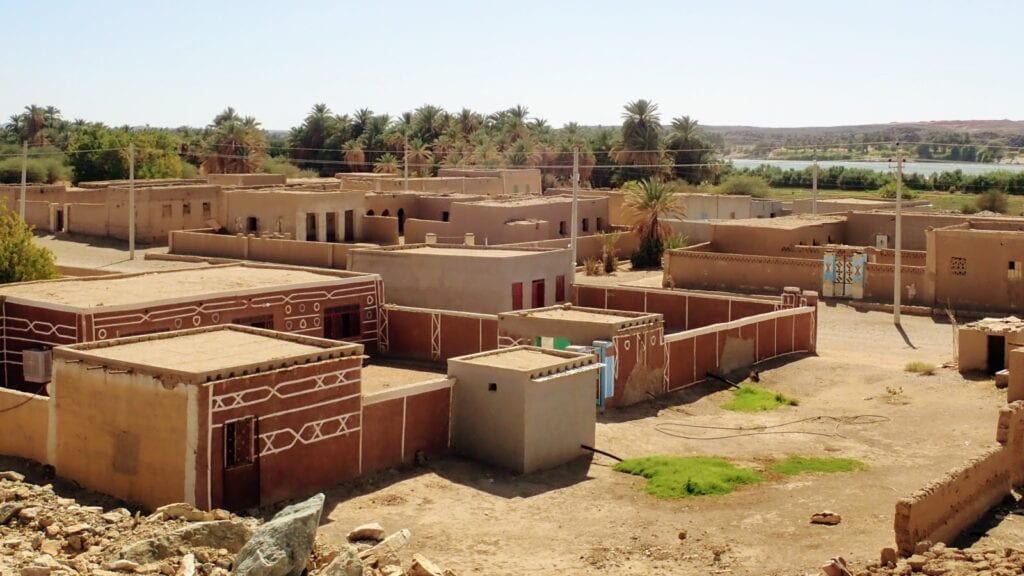

A large group of kids swept me off the highway and through the sand. My bike was leaned against a wall and I was whisked into the shade of a clay hut lined with basic rope beds. The patriarch was surprisingly adept with the Google Translate app on my phone and we “talked” while the whole family crowded around. We traded the usual simple questions, like how many children we each had. Me: 0, Sudanese Patriarch: 28. Everyone: uproarious laughter.

The head of the family seemed open and educated, and somehow a bit different. I longed to understand more, but could only parse something about “tribal problems.” Sudan is home to people from hundreds of different tribal affiliations and ethnic lines, and they don’t all get along. The worst conflicts are currently ongoing in the Darfur region, a no-go area for tourists, but apparently other issues simmer beneath the surface.

They offered to slaughter a sheep and host me for the night, but it was only 10am and they seemed like they needed all their sheep. I left them with a few pictures of myself and my family and pedaled on toward Karima, enjoying the solitude of the desert highway after all the attention but feeling very grateful for the interaction. In Karima I visited the ancient pyramids (smaller than Egypt’s but just as old, as locals proudly point out) and binged on cold boxed milk, falafel sandwiches, and chocolate pudding cups.

The next three days to Atbara were even hotter and harder than the first crossing. Though deceptively flat and well-paved, it was some of the most mentally challenging riding I’ve ever experienced. Twenty five pounds of water made the bike sluggish and heavy, yet the water was always hot and offered no relief.

A few tiny villages fought for survival in the impossible landscape, but there was little else to distract from the midday sun. Once I saw women carry jerry cans to the road to beg for water from passing trucks, and also from me, as if I had any to spare.

I reached gritty Atbara feeling dehydrated and weak, having underestimated my food supply for the three day crossing (one can only eat so much bread and cheese). An unwell-looking man made a grab for my bike as I passed, the first negative interaction I’d had in Sudan. I was grateful to the watchful shopkeeper who chased him away. When I finally found a friendly cheap motel, the owner kindly drove me through chaotic streets to the market where I could restock on food.

The next day I spent time in the common room with the owner’s family, a nice man who took my bike out for a hilarious wobbly spin, and an unusually confident young woman unlike any I had met in Sudan so far. The progressive influence of Khartoum, the capital city now just a couple days’ ride away, was beginning to show.

Being Female in Sudan

Gender roles in Sudan are a loaded topic. Until only recently (September 2020) Islam was the official state religion and strict Sharia-inspired laws imposed a very conservative culture. Women were legally required to cover their hair in public, forbidden from wearing pants, and restricted from activities like dancing, selling goods in the street, and some types of traveling unaccompanied by a male guardian.

In 2019 the oppressive ruler al-Bashir was overthrown, initiating a shaky march toward civilian rule and a less extreme version of Muslim culture. The transitional government has since repealed some of the oppressive “family laws” and criminalized the ubiquitous practice of female genital mutilation, both positive steps even if enforcement is practically impossible.

Closer to Khartoum I began meeting women with a distinctly different demeanor, still covered head to toe but walking alone or in groups, laughing and chatting, even approaching me to talk. In the university town of Shendi I saw a woman driving a car! In Khartoum I saw women removing their headscarves in high-end restaurants. I began to understand how and why women had played a significant role in the Sudanese revolution.

So what about me, a cultural aberration as a woman traveling alone, wearing pants, and riding a bicycle? As a foreign woman, “honorary man” status applies as well in Sudan as anywhere. I was welcomed warmly by most men and women alike, and granted privileges of both genders: the trust and protection generally offered to women, and the freedom and respect granted to men.

Still, my gender was a constant factor. I longed for more interaction with women but found it difficult; not all of them recognized me as one of them. One man pulled his motorbike over to ask “woman or boy?” Surprised but not unhappy with my answer, he handed me a black stone from his pocket, a good luck charm of sorts, and sped off with a wave.

Not all interactions were positive. On the outskirts of Khartoum’s suburbs I woke to a man reaching for my tent zipper with a clear proposition. He knew the English word “alone” and a hand gesture for “together,” and it was obvious what my status as a solo female traveler implied to him. I shined my headlamp in his face and repeated the Arabic word for “no” until he left.

The final day of riding was a fight through endless gritty suburbs and chaotic traffic into a hot sandy headwind. My tire went flat in the worst possible place and a group of men gathered immediately. I dreaded the usual interference but surprisingly they didn’t try to take charge. They simply offered a hand when appropriate, waited to see that the new tube held air, and moved on with their days – how refreshing!

It was a massive relief to reach the calmer streets of Khartoum’s upscale neighborhoods. I ordered a cheeseburger and chocolate milkshake, the first I’d seen in Sudan, and scarfed them down in celebration. While I was riding the desert highway a German woman had pulled over, offered a cold Coke (pure bliss!), and told me to call her when I reached Khartoum. I took her up on the offer, and by evening I was luxuriating in her upscale expat apartment, air conditioning and all.

Racing to Get Home

By then it was mid-March. As Khartoum reconnected me with the rest of the world, I could see things had changed while I was out wandering through the Sahara. COVID-19 outbreaks had been reported in touristy parts of Egypt not far from where I had been, and some countries were already restricting international flights. My German host was plugged into Khartoum’s expatriate network and relayed that some were making arrangements to leave before it might be too late.

In every other way though, things felt normal in Khartoum. Locals insisted it was “too hot for corona” and everyone felt sure the virus had not yet found its way into Sudan. Back at home my family members were stockpiling canned food and messaging me in alarm to say they couldn’t find hand sanitizer or toilet paper. Among the westerners I met in Sudan, a country that largely doesn’t use toilet paper for cultural reasons, the same dark joke kept coming up: let’s buy up all the TP from the expat shops in Khartoum and smuggle it home to sell for profit!

Obviously I wouldn’t be continuing to Ethiopia, which was actually ok with me. My trip felt complete already. I wasn’t in the mood to brave the notorious rock-throwing children of Ethiopia’s highlands anyway.

I booked a flight home for two days later, which felt risky. What if more flights were canceled in the meantime? But I had just biked from Egypt to the capital of Sudan. Impending global catastrophe or not, I wanted to spend a couple days enjoying the finale.

My wonderful host had another surprise up her sleeve: she knew the archaeologists in charge of excavating and maintaining some of Sudan’s temples and pyramids. During the days we explored ancient Nubian sites with the most knowledgeable of guides. In the evenings we sat inside the compound’s mud brick walls drinking tea (and a bit of illegal local palm wine – shhh) and trying to make sense of the state of the world.

As we drove back to Khartoum a few of the police at the checkpoints were wearing masks. But they still joked “too hot for corona” with smiling eyes as they waved us through.

Back in Khartoum I scavenged cardboard scraps from a furniture store and wrapped my bike for the flight. A few wealthy Sudanese were looking for hand sanitizer in the grocery store as I picked up one last round of snacks. I nervously refreshed the news and checked my flight status all evening, half expecting it to be canceled at the last minute. I would be connecting through Istanbul, and if Sudan, Turkey, or the US suddenly changed their rules I could end up stuck.

The small Khartoum airport was chaotic the next morning as expatriates, travelers, and a few wealthy locals waited anxiously outside the doors. We pressed close together, no one wearing masks. Back then the CDC was saying they weren’t helpful, and no one had them anyway. It was a relief to finally board the packed plane to Istanbul, and then the long haul flight to San Francisco. I went through a lot of hand sanitizer on the flights and in the airports, while thinking very little about distance and ventilation.

When the wheels finally touched down in San Francisco the relief inside the plane was palpable. I turned on my phone and received two messages: one from my husband saying our county had just imposed stay-at-home orders, and one from my friend in Khartoum saying all future flights from Sudan had been canceled that morning! I had very nearly cut it too close.

My husband picked me up, but after five weeks apart we didn’t hug until I had showered and changed clothes. I mostly stayed in a spare room for several days, but it’s embarrassing now to think of how little we knew back then. We washed our hands obsessively and sat at opposite ends of the dinner table, but didn’t even think to wear masks most of the time.

Pandemic Perspective

We all know how the rest of 2020 went, and I’m certainly among the luckiest in many ways. Being confined to home is much easier when you’re thankful to be there in the first place, instead of stuck in a place with questionable healthcare standards waiting for a repatriation flight. After a challenging bike trip I always retreat a bit anyway to recover from the physical and psychological strain. It was surprisingly easy, probably too easy, to slip into isolation.

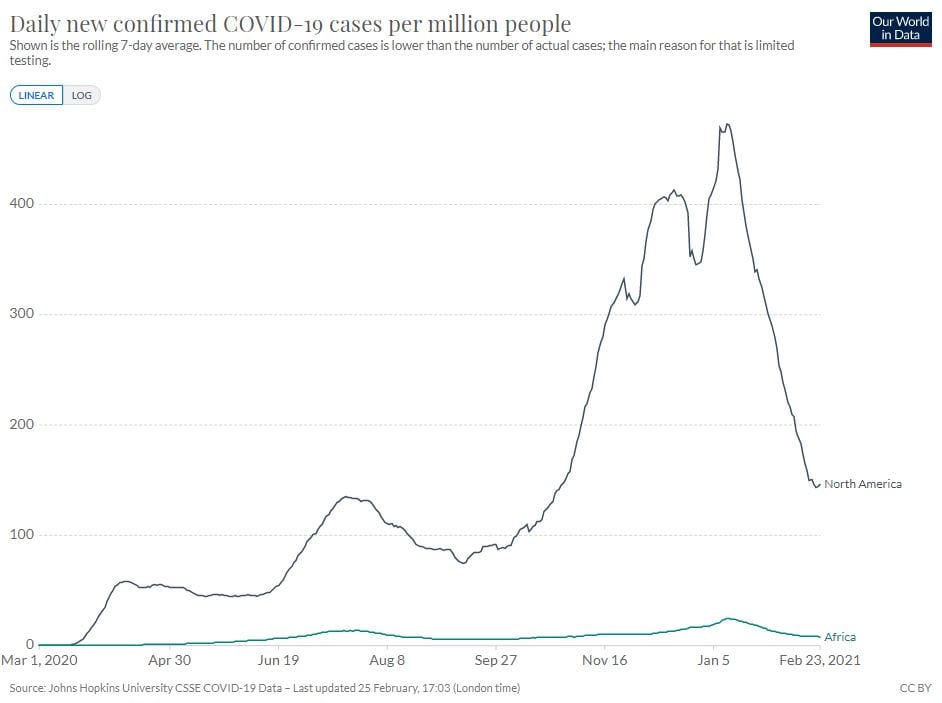

My pandemic experience has certainly been dominated by the situation in the US. But having been in Sudan when it started, I feel more closely tied to the global situation than some others might. I’ve watched the case counts in Sudan, Uganda, Sierra Leone, and other places I’ve visited, noticing how they remain barely visible near the bottom axis of the graph while the US and Europe spike.

By the numbers it looks like some of the world’s poorest nations, who usually bear the burden of disease most heavily, have been partly spared by COVID-19. Sub-Saharan Africa finally has some factors in its favor: young average age, limited long-distance travel, warm climate, and a lifestyle that includes plenty of time outdoors. In these places where so many people live hand-to-mouth, lockdowns could potentially kill more people than they save.

Yet it doesn’t take a data scientist to realize cases and deaths are not being accurately counted in these countries. During my time in Khartoum, when the US had already recorded tens of thousands of COVID-19 test results, Sudan had just received its first batch of a couple hundred test kits. For the entire country.

If people are dying of mysterious causes in remote villages, as they already do anyway, would they show up in COVID-19 death counts? On a continent where roughly 100,000 people die of malaria each year, perhaps COVID-19 is just another problem on a long list of serious problems. We may never know the extent of the damage in some places.

One positive takeaway from this horrible ordeal, in my opinion, has been a sense of global connection. Even as we shut our borders, we follow each other’s case counts and vaccination progress, and feel inspired by each others’ positive stories. The rapid global spread has made the true extent of our interconnection all too clear.

As we begin, hopefully, to emerge from our dark days here in the US, let’s not forget our neighbors across the borders and oceans. Our fates are intertwined, and our problems – COVID-19 and others – aren’t truly solved until they’re solved for everyone.

If you’re interested in riding this route when the time is right, see these more practical posts on cycling in Egypt and cycling in Sudan for the logistics and details. You can also learn more about me and my bike rides at exploringwild.com.